🌍 Where There Was Salt, There Was Us

If you map the world by access salt, you’ll notice that salt wasn’t a luxury; it was a proxy for survival, a geologic signal that told bodies where to go and communities where to stay. We didn’t just want salt. We needed it. Salt meant survival. It preserved food through winter. It powered trade before coins. It let humans settle - and stay. Salt gave us the ability to store energy, move goods, and feed cities. Without salt, there were no cities. No civilization.

Animals etched the first lines, herds looping back to lick the ground alive, and we traced their circuits, setting camps where fresh water met salt and watching the hunt take shape along those edges.

Some of our oldest human footprints are pressed into the margins of alkaline lakes; they read like wayfinding notes in the sediment.

Paleolithic sites cluster around salt sources because salt turned a place into a pantry, a clinic, and a trade post at once: it made meat last, kept nerves firing, and drew neighbors who carried news and goods.

Even burials traveled with salt, a ritual compass pointing to what sustained us.

Long before we drew maps, craving pulled the routes taut - caravan lines, river crossings, seasonal loops - until “home” cohered where the gradients were right: enough sweetness to drink, enough salt to live. Follow the salt, and you can read how we learned to live in place.

The Animal World

As we have learned, salt isn’t optional - even for animals. It’s the charge behind nerves, muscles, and survival. On land, where plants and soils are often sodium-poor, animals must get creative. Their cravings leave visible trails on the landscape.

-

A 5-ton needs about 45g of sodium daily (~3 tbsp of salt).

Young bulls can chisel 30–40 lbs of salty cave soil in under an hour.

Daily salt-seeking treks span 10–30+ miles, and Congo forest elephants have been tracked migrating ~155 miles (250 km) between forest clearings rich in salt (baïs).

Mine Deeper:

Salt Seekers of Anakulam – YouTube

Inside an Elephant Cave – YouTube

-

In Uganda’s Bwindi forest, dead wood makes up only 4% of gorillas’ diet but provides over 95% of their salt.

In Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, eucalyptus bark delivers up to two-thirds of their sodium salt.

Some even venture into harsh sub-alpine zones to chew giant groundsels and lobelias—salt forces their movement

-

Nectar is sweet—but sodium-poor. So butterflies seek mud, dung, sweat, carrion, and even animal tears.

Male butterflies transfer up to 1/3 of their sodium stores during mating.

Some species, like Gluphisia crenata, eject fluid every 3 seconds, expelling up to 600× their body mass post-puddling.

Mine Deeper:

Commander Butterfly Salt Lick – YouTube

-

Before domestication, wild aurochs roamed from Europe to North Africa, guided by salt licks, springs, and rivers. Over time, these cravings became migratory memory, trails taught across generations.

Like elephants and deer, they used geophagy and licked rocks and bones to replenish sodium lost through sweat and lactation.Even after domestication, cattle retain these instincts—wandering miles when salt is deficient, chewing bark, licking urine.

Today industrial farms simulate ancient solutions with salt licks, which are strategically placed near water, echoing ancient migrations.

🗺️ The Map of Craving

So what if we redrew history, not by war or empire, but by our craving for salt?

🐘 Animal migration trails

🏞️ Prehistoric salt paths

🧑🏽🌾 Early human migrations

🌊 Coastal communities drawn to brine-rich zones

Just as salt enables neural signals in our brains, it also sends signals across the planet, guiding life toward it. These trails formed a biological network of survival - etched into terrain like veins, like memory.

Salt is pattern, path, and pull - a map hidden in plain sight.

Salt didn’t just make us move. It made us build.

From the brine boilers of Neolithic China

to the Roman Salt Road (Via Salaria),

from Himalayan yak salt caravans

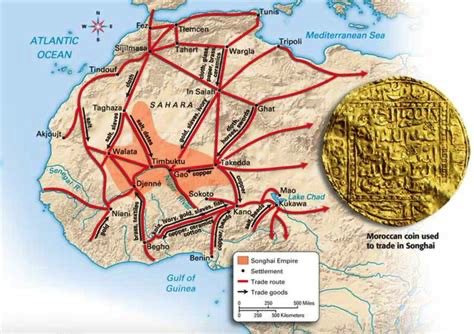

to the salt-gold economies of West Africa—

the craving for salt became the foundation of civilization itself.